The death of French nun Lucile Randon, known as Sister André, at age 118 — in fact, 25 days short of her 119th birthday — has revived the perennial question: how long can a person realistically hope to live?

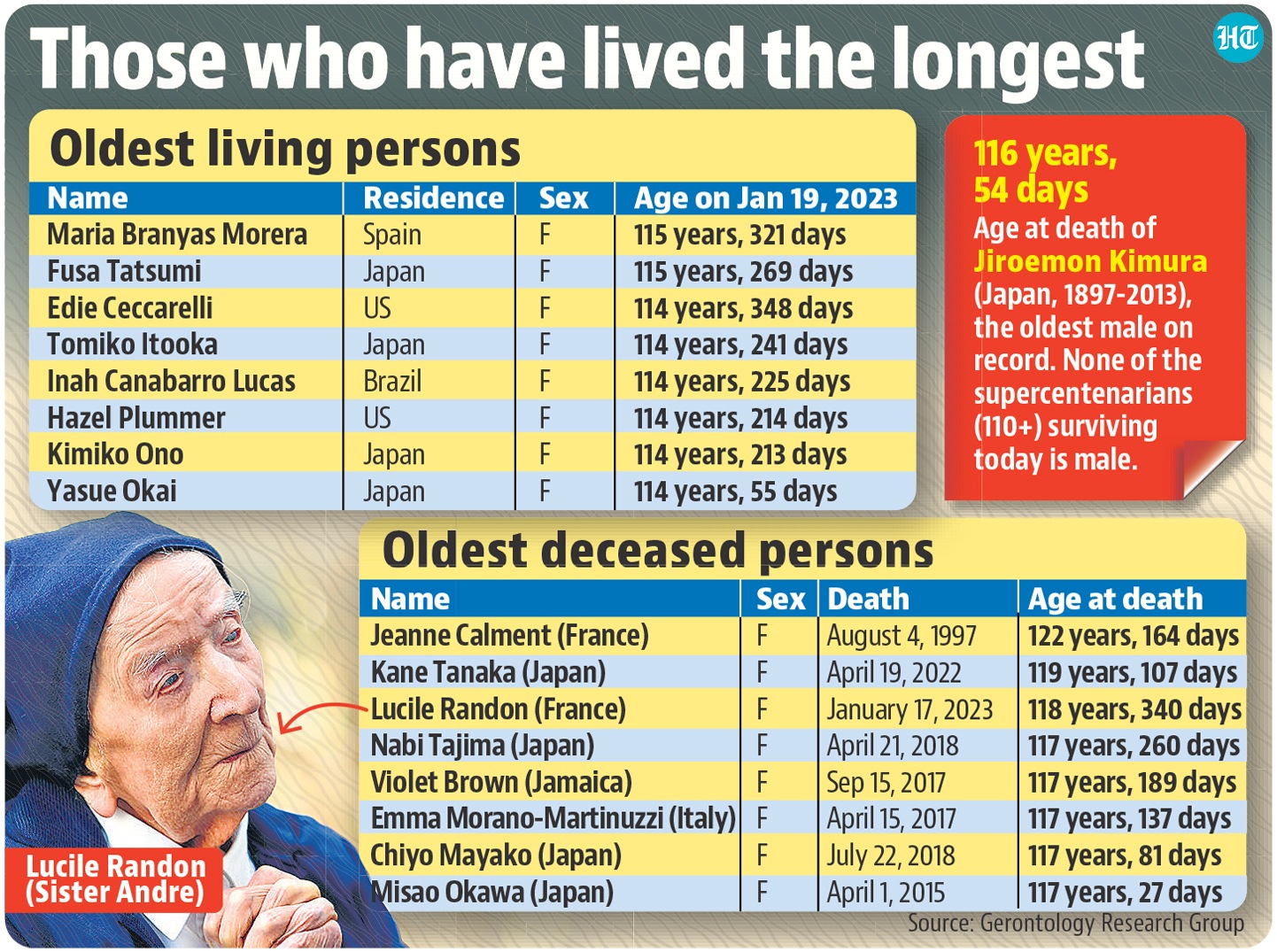

Sister André, the oldest living person until her death on Tuesday, held that mantle since April 19 last year, following the death of Japan’s Kane Tanaka at age 119 years and 107 days. It now passes on to Spain’s Maria Branyas Morera, whose 116th birthday falls on March 4.

Also Read: World’s oldest known person, French nun Lucile Randon, dies aged 118

Tanaka led the second longest life on record, behind only France’s Jeanne Calment, who was 122 years and 164 days old when he died on August 4, 1997. Given that the record has stood for 25 years, is it realistic to expect that it will ever be broken?

It apparently is. Recent research has projected that it is near certain that the record will be broken during the current century. Another study put a limit to life expectancy at 150 years, but a lot of things have to work in favour of a person to live that long.

Other research, meanwhile, continues to keep the debate raging. Some findings suggest there is no upper limit involved. Others stress that ageing (and consequently death) is inevitable, even though people are living much longer today than they were a few centuries earlier.

The projection that the record of 122 years is set to be broken came in a study published in June 2021, when Tanaka was 118 years old and Sister André had just crossed her 117th birthday. Using statistical modelling, researchers from the University of Washington projected that it is:

● Nearly 100% probable that the record will be broken by the end of the century;

● 99% probable that someone or the other will live up to 124;

● 68% probable that even the age of 127 years will be breached; but,

● Only 13% probable that anyone will live up to 130.

The last of these projections need not necessarily be a dampener. Even if the probability of living up to 130 is low, the theoretically possible limit is as high as 150 years, according to another study, also published in 2021, this one in Nature Communications.

The two studies reached their respective conclusions using vastly different approaches. While the one from Washington University was statistical, the other one was based on biology.

Researchers from Gero, a Singapore-based biotech company, in collaboration with Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, US, used an index called DOSI, based on complete blood counts, to measure the ability of people to recover from various stresses, such as illness, strenuous exercises and lack of adequate sleep. Extrapolating their findings from study subjects, they found that human body loses its resilience completely at some age around 120-150.

The caveat is that these projections are for individuals without any major illness.

The modelling study used a tool called Bayesian statistics and a database of individuals in 13 countries to calculate what the longest individual human lifespan could be in the year 2100. Its calculations were based in part on the observations that one’s chances of survival flattens out after a point.

That is to say, a 10-year-old may have a much higher chance of surviving another year than a 90-year-old has of living to be 91, but the difference is narrow between people of very high ages. To illustrate with an example, the oldest living person today, Morera, who is almost 116, has as much chance of living to 117 as the eighth oldest, Japan’s Yasue Okai, who is 114, has of celebrating his 115th birthday, going by the findings.

At those advanced ages, the chance of surviving one more year is roughly 50:50 whether the individual is 110 or 115. Needless to say, it does not remain 50:50 across longer periods: if an individual’s probability of surviving one more year is 50%, then their probability of surviving a second year reduces to 25% (when calculated today), and so on. Hence the differences in projections for someone living up to 122, 124, 127 and 130 years.

The chances of surviving from one birthday to the next flatten out to 50:50 at around age 105, according to an earlier study, this one published in Science in June 2018. It derived its findings from data on all Italian individuals aged 105 or more, and concluded that this plateauing of mortality risk implies that there is no upper limit to human longevity.

That does not by any means end the debate. In June 2021, yet another study in Nature Communications tested the “invariant rate of ageing” hypothesis, which essentially means that the rate of ageing is more or less constant among adults of any given species. Using the index DOSI to analyse data from 30 primate species, including humans of diverse populations, the researchers concluded that the hypothesis is true.

The University of Oxford, whose researchers were part of this study, summed it up with a statement: “You cannot live forever: Ageing is unstoppable.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading