Lithium is often described as the white gold of energy storage technology; light and compact, it is the defining element in the lithium-ion batteries that drive our mobile phones, laptops and, in some cases, electric cars. The development of such batteries, in fact, was considered important enough to fetch the 2019 Nobel Prize for Chemistry to scientists John B Goodenough, M Stanley Whittingham, and Akira Yoshino.

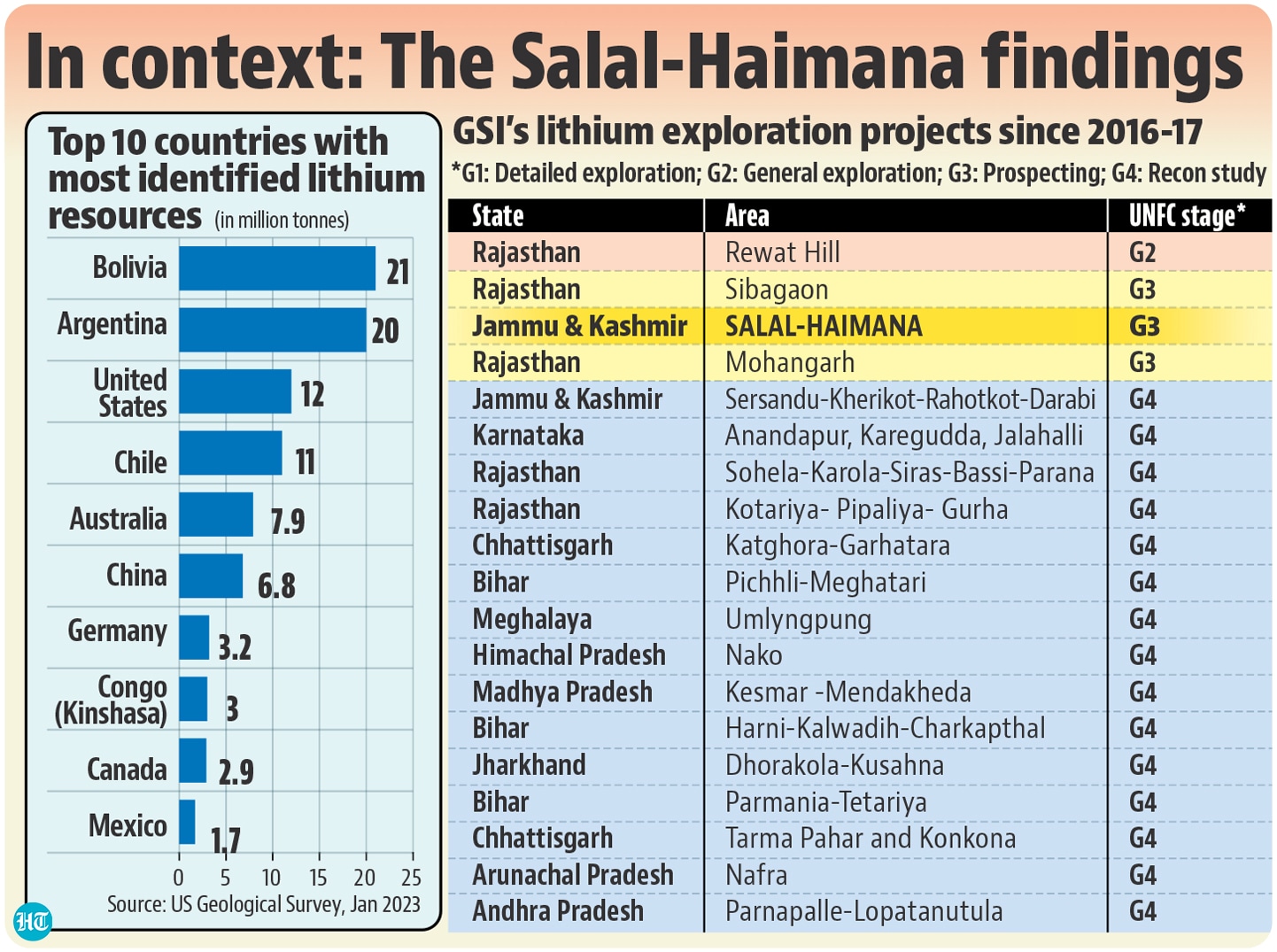

Our reliance on lithium-ion batteries explains the excitement around the Union ministry’s recent announcement that the Geological Survey of India (GSI) has established lithium inferred resources of 5.9 million tonnes in Salal-Haimana of Jammu & Kashmir. For a country that depends largely on imports for lithium as well as lithium-ion batteries, the inferred size of the resources can raise hopes for self-reliance.

That is, provided there is as much lithium as is being inferred, and that all or much of it can be extracted.

Also read | Lithium found in Jammu and Kashmir ‘of best quality’

Why ‘inferred’?

It is a long road between “inferring” a large amount of lithium, and actually getting to use it. The term, as it suggests, means the estimated lithium content is yet to be established. And even if it is, the next step would be a complicated task in itself: extracting the element from its source.

“Inferred resource” broadly means that the quantity of a mineral can be estimated on the basis of geological evidence, but it remains to be verified. In other words, the estimates for Salal-Haimana are of estimates “of quantities that are inferred, based on interpretation of geological, geophysical, geochemical and geotechnical investigation results”.

“It is only an inferred resource right now. It needs to be worked upon, an extraction method has to be decided. It’s a good finding but where it will lead to, whether we can mine it or not, we are not very sure,” said Shashank Shekhar, professor of geology in Delhi University.

Again, the resource has been classified G3. Under the UN Framework Classification (UNFC) for minerals followed by the ministry of mines, G3 is the second of four stages: preliminary exploration. Much will depend on the subsequent stages of general exploration (G2), and detailed exploration (G1).

Complicated extraction

Globally, two major methods are used for large-scale extraction of lithium: the evaporation of brine at salt pans, and crushing hard rock. An alternative being explored is recycling of used lithium-ion batteries.

Evaporation, which involves a series of steps for chemical treatment and purification, is a time-consuming process, but it is much more widely used than the rock extraction process. Chile, Bolivia and Argentina, which form the “Lithium Triangle” that holds the bulk of the world’s reserves of the metal, have an abundance of the metal in their salt pans.

Extraction from ores is a more complex process, and it is in ores in Jammu & Kashmir that a large lithium content has now been inferred. The process involved crushing and roasting the ore at temperatures beyond 1,000°C, then cooling and roasting it again with sulphuric acid, and finally the addition of lime for the removal of impurities and extraction of lithium carbonate, which will later be converted to other lithium compounds for use in batteries.

Nevertheless, Shekhar said: “It all depends on the type of technology you use. I think with all precautionary measures, if it is environmentally sustainable, that (the finding) is a good indication.”

There may, however, be environmental issues. “It’s a forest area so mining might be difficult,” he said.

More potential sources

Salal-Haimana is one of several sites where GSI is carrying out lithium exploration programmes. Between 2016-17 and 2021-22, the number of such sites was 19, including Salal-Haimana, according to details tabled by the ministry of mines in the Lok Sabha in March last year.

On February 8 this year, days before its newest announcement, the ministry told the Lok Sabha that GSI has carried out 20 such projects in the last five years.

All the sites listed in the 2022 reply contained lithium in combination with other substances. The Salal-Haimana site, for instance, contained lithium, bauxite, and rare earth elements. It was already designated G3 then, alongside two sites in Rajasthan, while the programme at Rewat Hill, also in Rajasthan, was at the more advanced G2 stage.

In addition, Khanij Bidesh India Ltd (KABIL), a joint venture of three central PSEs, is exploring opportunities for investment in lithium mines in Argentina and Australia, the ministry said last week.