As 2023 draws to a close, it rounds up an unusually turbulent three years that saw multiple black-swan events: a once-in-a-century pandemic, two bloody wars, sticky global inflation, and growing protectionism that threatens to upend both the post-pandemic recovery and the long-held consensus on globalisation.

2024 will be a year of elections in 40 countries, from Taiwan in January to the United States in November. Lok Sabha elections are expected in April-May, and the build-up to the vote and the possibility of the new government recalibrating the economic agenda has multiple implications for the Indian economy.

These include the impact of the pre-election spending stimulus that could potentially revitalise flagging consumption, at least in the short term, in redirecting the debate on welfarism versus trickle-down growth, and in reinvigorating the growth momentum against a backdrop of widening cleavages in the recovery story.

There are also worries around food inflationthe sluggishness in rural output and services sector growth, and the question of how best to capitalise on India’s demographic dividend while riding the new technology wave.

Elections and capex impact

No easy answers may be available. Goldman Sachs, the US-based investment bank, has predicted a pick-up in growth in the first half of next year, driven by a consumption spending push in the run-up to the elections — and a possible rekindling of investment growth in the second half, with private investment finally kicking in.

However, economists have also projected a possible slowdown in the momentum of government capex — a sustained driver of growth — as the elections approach, which could constrain growth outcomes for the next year and aggravate the sluggishness in rural growth, with serious implications for the consumption outlook.

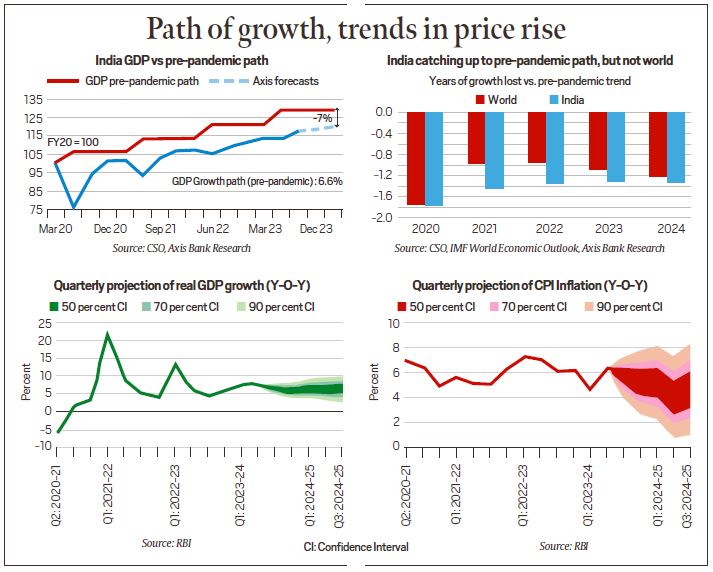

According to Axis Bank research, India’s output gap vs the pre-pandemic trend has narrowed to 7% until December 2023, and in terms of the number of years of growth lost, it has caught up to the global average. But there is still a gap — and from a statistical perspective, a normalising base for the GDP data could be a potential bugbear for policymakers.

The FY24 second quarter GDP print did offer some clear positives: the growth in the construction sector that surprised on the upside; the mining and electricity segments, and utility services witnessing double-digit expansion; declining commodity prices; and the investment rate (measured as the nominal investment to output — Gross Fixed Capital Formation-to-Gross Domestic Product — ratio) surging to 30%, which was the highest in any second quarter period since the second quarter of FY15.

The growth momentum in the markets, both primary and secondary, are a signal that investors, especially domestic investors, are willing to bet on listed companies and the ones getting listed. The mutual fund sector and insurance companies have become sizable investors, even absorbing selloffs by Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPIs) in the capital markets. But this advantage is limited to a small sliver of India’s enterprise base — formal sector firms and companies that have the wherewithal to tap the capital markets.

Several lingering concerns

But a more fundamental problem that is now being talked about in policy circles is this: the Indian economy suffers from a very narrow base to support high growth rates that is, especially after 2016, clearly reflected in the small share of the consuming class with significant discretionary incomes, low bank credit as a share of GDP, a relatively low level of investible financial savings, a missing middle of productive small and medium-sized enterprises that create the majority of jobs, and an acute scarcity of good-quality skilled workers.

In the absence of these growth factors, India is becoming an economy with a small group of highly productive firms and employees, and high consumption in this specific category. The vast majority remains stuck in poor productivity and subsistence consumption, and this trend has intensified after 2017-18, with the negative shocks of demonetisation, GST, and the pandemic having a lingering impact on an economy that has a large informal sector, and one that was already on the downswing.

This is reflected in the unemployment situation, which the think tank Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) projected at a high 9.2% in November 2023, and which the opposition flagged repeatedly during the campaign for the recent Assembly elections. While the recently released edition of the government’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) counters this narrative, worries about jobs seem reflected in the demand across states for quotas, and the increasing promises of freebies from almost all parties now.

Headline indicators for India have been stuck at the same level for several decades — bank credit to GDP ratio at 50-60%, central tax-to-GDP ratio at 10-12%, manufacturing as a share of GDP at 15-17%, savings rate at 28-32%, Gross Fixed Capital Formation (a proxy for investment impetus) at 26-30%, according to an analyst who previously worked for the central government.

The challenge before the new government would be to change this, and to revitalise stalled reforms — genuine reforms involving factors of production. While land and agri reforms ground to a halt, a template for reviving labour reforms is now ready to be put in motion: the four labour codes, a comprehensive rollout of which is now most likely only after the elections.

In the electricity sector — a big driver of capex — there is a change in the policy that was focused almost entirely on renewable energy for incremental capacity addition, with fresh coal-fired capacity virtually ruled out. Now, with renewables accounting for a large chunk of the installed generation capacity, there is an emerging policy consensus that in the absence of storage, incremental renewable power capacity poses problems for grid managers. This is forcing a pivot back to thermal or nuclear generation to meet base load demand, and portends a period of policy flux and supply side concerns.

Multiple tailwinds for India

Fortunately, there are multiple tailwinds, both internal and external.

Against a backdrop of global economic volatility, the Indian economy does present a picture of resilience. GDP growth during the second quarter exceeded all forecasts and the fundamentals of the Indian economy, according to the Reserve Bank of India, remain strong.

Banks and corporates are showing healthier balance sheets, fiscal consolidation appears to be on course, external balance is manageable, GST collections remain buoyant, and there is adequate forex cushion against external shocks. These factors build on the fundamentals that make India a top driver of global growth.

Unsecured loans have, however, emerged as an area of concern for regulators. Fintechs have taken advantage of lax regulations to peddle loans to consumers with loose screening, which now run the risk of turning into NPAs. The RBI has now started clamping down on unsecured loans.

Chief Economic Adviser (CEA) V Anantha Nageswaran says India’s growth rate can become faster if private capital formation moves into higher gear. According to the CEA, the public sector has done its part, and there are enough resources with the private sector, with a positive financial balance of the private corporate non-financial sector.

“Because of Covid, the war in Ukrainethe private sector has been cautious but unless investment activity leads to employment generation, which in turn, leads to income growth which in turn will lead to sustained consumption, the growth engine will not be revived,” Nageswaran said at a session on ‘Revving up the World’s Growth Engine’ at FICCI’s 96th Annual General Meeting on December 13.

“Consumption is a consequence of economic growth,…not the cause for economic growth. (For)…economic growth…we need to have investment spending, which in turn leads to other positive benefits such as employment and income and eventually consumption growth. …Having done the balance sheet repair,…shored up the financial position,…seen capacity utilisation rates hit levels which in the past have necessitated additional capacity expansion, private capital formation is the most important catalyst to rev up the growth engine. The public sector has done its part and it will continue to do so,” he said.

Neelkanth Mishra, Chief Economist, Axis Bank, expects upgrades to India’s GDP forecasts, as continuing positive surprises force an upward reset in trend-growth assumptions. Global headwinds, though, are likely to intensify, as US growth in 2023 was boosted by an unsustainable fiscal support, according to Mishra.

Also, volatile food inflation is likely to keep headline inflation elevated, with high- frequency food price indicators pointing to an increase in prices of key vegetables. This may push CPI inflation higher in the near term, including wheat, spices, and pulses among the rabi crops, he said. High global sugar prices are also seen as a concern.

While a major challenge for India — and all economies with current accounts in deficit — is the crowding out caused by sustained high fiscal deficit in the US, the increasing likelihood of the US economy heading to a soft landing (in which inflation would fall without a rise in unemployment or a recession), and the Federal Reserve’s projection of three rate cuts next year, are a positive that could lead to foreign investors pumping back money into emerging markets such as India.

FPIs have already made a major comeback to India in December, and growing indications of stability and continuity after the 2024 elections is yet another positive. While the global economy is showing signs of slowdown, RBI officials maintain that the Emerging Market Economies as a group have remained resilient during the current round of volatility, unlike in previous episodes. Evidently, India is better placed to withstand the uncertainties compared to many other countries.

While headline inflation has receded from the highs of last year, core inflation continues to be sticky, impeding the last mile of disinflation. Major central banks, including the RBI, have kept rates on hold while refraining from forward guidance in view of prevailing uncertainties. Financial markets are projected to remain volatile as they seek out definitive signals about the trajectory of interest rates. Greater certainty is likely on this count in 2024 — unless another black swan event were to impede the growth momentum yet again.