Saying that the proposed disclosures about the promises and their implementation would help voters make informed choices, the EC has set October 19 as the deadline for submission of responses by the political parties, many of which immediately bristled at the move.

The proposal comes amid a raging debate over freebies, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi decrying what he has called an irresponsible culture of distributing sops like “revadi”. Many in the opposition criticised the suggestion for regulating freebies and have argued that they were needed to provide relief to the underprivileged.

The SC is also hearing a petition seeking regulation of freebies which has been opposed by parties and state governments.

The litigation is unlikely to have any impact on the EC’s move to build standardised disclosures on poll promises into the model code of conduct (MCC), which has no legal backing and is only a voluntary understanding between the EC and the political parties that comes into play during the election process. The EC will release the new guidelines once the consultations with the parties are over, though this may take some time as it is not unusual for parties to seek extension in the EC deadline to submit their opinion.

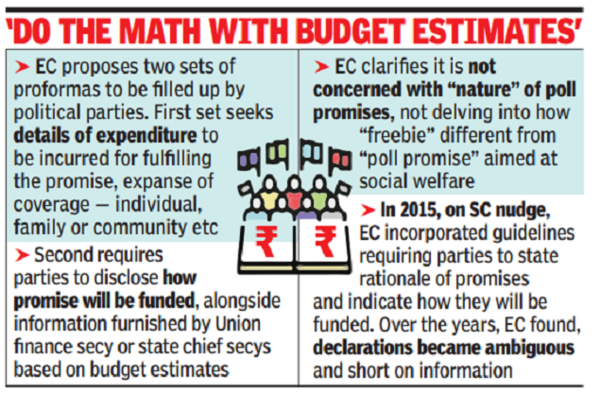

There is no existing law that regulates poll promises. But EC in 2015, as directed by Supreme Court in the Subramaniam Balaji case, did incorporate the guidelines on manifestos into the MCC. They require parties to reflect the rationale of the promises and broadly indicate ways and means to meet the financial requirements.

However, the EC over the years found the declarations to be ambiguous, routine and short on information that can help the voters make an informed choice.

At a full Commission meeting here on Tuesday, chief election commissioner Rajiv Kumar and election commissioner Anup Chandra Pandey agreed that the EC cannot remain a mute spectator to the “undesirable” impact of some of the poll promises and offers, on the conduct of free and fair elections and maintaining a level playing field. “A prescribed format for disclosure… is necessary to bring standardisation in the nature of information and for facilitating comparability,” it stated.

Keeping in view the parameters followed by Finance Commission, RBI guidelines, Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, CAG principles and preparation of the general budget — all familiar domains for the CEC, a former Union finance secretary — the EC has proposed two sets of proformas to be filled up by the political parties. The first requires details like promise-wise expenditure and expanse of their coverage. In the second proforma, parties must disclose how the promises are to be financed, alongside pre-filled fiscal information furnished by Union finance secretary or state chief secretaries based on latest budgetary estimates or revised estimates in the election year. The official data, a senior functionary pointed out, will also help the voters gauge how the fiscal health has been under the party seeking a re-election.

The EC made it clear that it was agnostic to the “nature” of poll promises, not delving into what defines a “freebie” or what distinguishes it from a “poll promise” aimed at social welfare. It said that it agrees in principle that framing of manifestos is the right of the political parties.

Among the details sought to be captured by the proformas for poll manifesto disclosures are extent of coverage of the promise (as in individual, family, community, BPL or entire population); quantification of physical coverage; quantification of financial implications of the promise; and availability of financial resources. The parties will need to disclose the ways and means of raising the resources, like an increase in tax or non-tax revenues, rationalisation of expenditure in terms of withdrawal of an existing scheme or benefits, additional borrowings and the impact of additional resource raising plan on fiscal sustainability of the Union or state government including the sectoral impact.