Bandyopadhyay was nominated in 1971 — the year Pablo Neruda won. We know this only now because Nobel nominations are kept secret for 50 years. There were 137 nominees for the literature prize that year, and the Nobel website says Bandyopadhyay’s name was sent by author Krishna Kripalani, who was secretary of Sahitya Akademi at the time.

Still A Relevant Voice

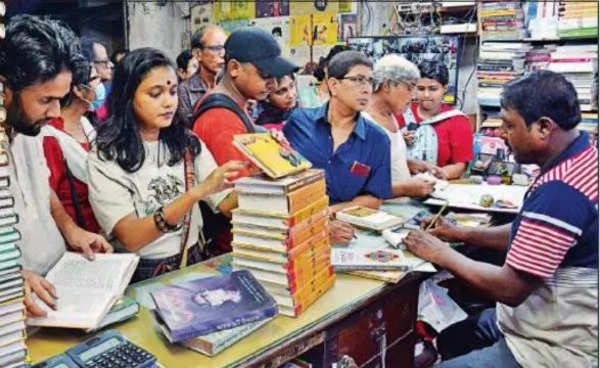

Bandyopadhyay wrote novels, short stories, poetry, lyrics, drama, memoirs and essays, and people identify with his deeply humane writings even today, five decades after his death. At Kolkata’s College Street boi para (book market), readers of all ages come to buy his classics, such as Hansuli Banker Upakatha, Kabi, and Ganadevata.

“We have 25 Tarashankar rachanabali (anthologies), which are in great demand. Single books are also sold throughout the year,” says 90-year old Sabitendranath Ray, owner of Mitra and Ghosh Publishers. The books still bring in Rs 3. 5 lakh in royalty for the Bandyopadhyay family every year, he adds.

Academic PabitraSarkar says Bandyopadhyay’s brilliance lay in making his readers uneasy by showing the hard-hitting reality. “In one story, a husband leaves behind his wife during a flash flood as she tries to hold on to him to save herself. The husband, in order to survive, just lets the wife drift because both will die if he takes her along. ”

He says Bandyopadhyay also feels contemporary because of his portrayal of subjects that were thought to be ‘untouchable’ in Bengali literature. “The character of Nassubala, who is biologically a male but behaves, dresses and feels like a woman, is one of the finest creations of the author. ”

Sumita Chakrabarti, a retired professor of Bengali, agrees Bandyopadhyay’s writings opened new vistas in Bengali literature. “His first novel, Chaitali Ghurni, was revolutionary because for the firsttime the protagonist, Gostha, belongs to the Sadgop subcaste. ”

If Hansuli Banker Upakatha speaks about the Kahar tribes, in Daini, a woman seen as a witch by society comes to believe she is a witch. “His writings reflected the lives of the marginalised, whichwas pathbreaking at that time. They remain relevant because we still have discrimination between upper-caste Hindus and Dalits,” says Chakrabarti.

Besides a penetrating eye, Bandyopadhyay brought great objectivity to storytelling. “Like Dostoevsky, he treated his characters unbiasedly, did not take sides, but was overall sensitive towards mankind,” adds Chakrabarti.

Bandyopadhyay works remain popular among readers, including at the College Street book market in Kolkata

Society’s Unbiased Mirror

Born in a zamindar family in Labhpur, Birbhum district, in 1898, Bandyopadhyay used his first-hand knowledge of the country to write about the people, the soil, cultivation, revenue, taxation, agricultural loans, crop failure, famine, flood and the back-breaking toil ofthe landless field labourers.

He was aware of the vast economic disparity between the classes, and the rivalry between old traditional families and newly-rich coal traders. These people, the dry, red soil of Birbhum, and the turbulent Kopai river were very important in the writer’s life, and his famous novels like Ganadevata and Hansuli Banker Upakatha highlight the rural topics and themes.

As a historical and politically conscious realist writer, Bandyopadhyay wrote about the transformations that were taking place in the rural society, his experiences of city life, national events like riot, famine and the Partition. India’s struggle for independence stirred him and he also joined the NonCooperation Movement. He was compelled to write about the goriness of the 1943 Bengal famine and the bloody destruction of the Great Calcutta Killings. “The impartial portrayal of riot and divisiveness, the fear among the people of both communities, make these writings universal,” says Chakrabarti.

Lost In Translation

But for all his pathbreaking writing, Bandyopadhyay is relatively unknown outside Bengal. Could the news of his Nobel nomination bring him wider recognition now?

Bengali scholar Athmajit Mukherjee says, had the nomination been announced in 1971 itself, it would have made Bandyopadhyay a more intriguing figure. “He was a unique figure who left his privilege to write on his political ideals. He faced a lot of hardship, including jail time for inflammatory writing that would be published in his printing press. ”

Prithu Haldar, literature scholar at IIT Kharagpur, says the information could have brought “pan-Indian recognition and popularity” to Bandyopadhyay had it been known earlier.

Bandyopadhyay’s grandson Himadri Banerjee, however, says “there is nothing to lament” in the belated disclosure. “The love and respect that the people of Bengal have given him, and his contribution to Bengali literature are immense. Moreover, it is not a new fact for us. ”

Another family member says the availability of good translations plays a big role in winning a Nobel prize, but Bandyopadhyay was at a disadvantage in this respect. Banerjee, who is a retired history professor, says many attempts have been made to translate his grandfather’s works, mostly without success.

Ray from Mitra and Ghosh Publishers agrees with Banerjee. He says when they tried to translate Ganadevata into English to acquaint more readers with it, they could not find a translator who would retain the original’s flavour.

But Sudipto Dey, one of the owners of Dey’s Publishing, says curiosity about Bandyopadhyay might spur the translation of his greatest works now — leading to greater recognition outside Bengal.

A Giant Of Indian Writing

Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay passed away in September 1971, a month before the Nobel prizes were announced. He had won West Bengal’s highest literary honour, Rabindra Puraskar, in 1955, and the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1956. In 1966 he received the Jnanpith Award for Ganadevata. He was also awarded the Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan in 1962and 1969, respectively.

Bandyopadhay’s ancestral house in Labhpur has been converted into a museum, and four years ago the Bangiya

Sahitya Parishad bought his house near Tala Park in Kolkata – where he breathed his last on September 14, 1971 — to turn it into a museum where his table, sticks, chairs and pens will be displayed.