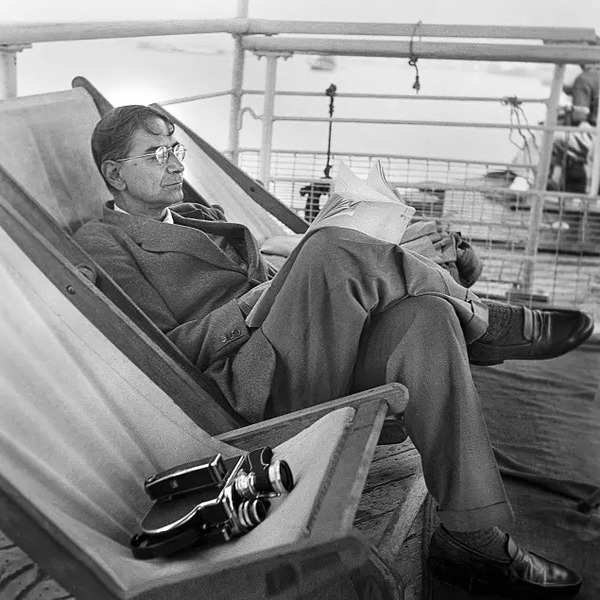

the man who taught the world the art of large-scale sample surveys

* What sparked your interest in writing a book on post-colonial Planning in India?

Believe it or not, there was a time when planning was fashionable—a buzzword. Five Year Plans were once a theme in Bollywood movies and songs! Why and how did planning become so central to the story of modern India? That is what my book,

Planning Democracy

is about.

* What was the series of events that saw P C Mahalanobis becoming India’s pioneering statistician?

Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis was one of the most influential Indians of his generation—a brilliant scientist, globe-trotting academic, and powerful technocrat. While training to be a physicist in Cambridge, his interest in statistics was sparked by a chance encounter with a journal of statistics in the library at King’s College. This led to a long transformation from being a physicist to founding the Indian Statistical Institute in 1931 and eventually becoming one of the foremost statisticians in the world. Meanwhile, as the Indian National Congress under Subhash Chandra Bose committed independent India to a planned economy, statistics on the economy was the need of the hour. Mahalanobis and the Indian Statistical Institute were optimally placed to deliver it, opening the doors to the Planning Commission.

* How would you describe his role in the making of modern India?

Mahalanobis and the Indian Statistical Institute were responsible for establishing India’s data infrastructure. They brought the first digital computers to India and designed the National Sample Survey, which continues to play a key role in policy-making to this day. Most significantly, perhaps, Mahalanobis was the author of the Second Five Year Plan (1956-61)—an enormously influential and controversial document which provided the blueprint that India’s economy followed until the market reforms in the 1990s.

* What was PC Mahalanobis’ most enduring contribution to the global statistical system?

Put simply, large-scale sample surveys. Angus Deaton, the Nobel prize winning economist, wrote that when it came to instituting sample surveys of household income and expenditure

,

“Where Mahalanobis and India led, the rest of the world has followed”. The World Bank’s flagship household survey program can trace its lineage back to India’s National Sample Survey.

* What does ‘Digital India’ owe to the pioneering statistician?

We must remember that in the early 1950s, computers were a new, extremely rare, and exorbitantly expensive technology. A single computer could cost a million dollars! It was also shrouded in mystery. This was because in the countries where they were being manufactured they were used for military purposes at first. Mahalanobis saw how useful they would be in helping with the National Sample Survey calculations and in planning and economic development. He spent nearly a decade criss-crossing the globe in their pursuit. When India received its first computers—from the UK and the Soviet Union—they were the direct result of his involvement.

* Was it easy for P. C. Mahalanobis to bring the first digital computers to India?

Not at all! Especially given their stratospheric costs and sheer rarity. Mahalanobis spent years explaining, cajoling, pleading with foreign governments, aid agencies, and the government of India. I even found evidence that the US government decided not to grant a computer to India because they suspected Mahalanobis to be a communist—a deal-breaker given the Cold War context.

* Can you give us a brief peek into both the highlight reel and the blooper reel of India’s first National Sample Survey?

Started in 1950, it was the biggest and most comprehensive sampling inquiry ever in the world. The challenges were enormous. The initial sample they arrived at was around 1800 villages out of India’s 5,60,000 villages. The Institute was short staffed, and needed to negotiate 15 languages and 140 local systems of measurement. Mahalanobis would write in his diary about forested areas in Orissa where investigators had to be accompanied by armed guards through forests, and snow-clad Himalayan passes to scale. In other parts, investigators often fell ill due to tropical diseases, or even feared for their lives because of man-eating tigers!

* Were there any aspects or anecdotes from his professional or personal life that stood out to you during your research?

There are too many to recount! But he was a fascinating personality and enormously influential. I found it amusing, for instance, that so many people simply referred to him as ‘The Professor,’ despite there being scores of other professors around. In terms of his personality, he was known to be serious (except with his pets which included cows, cats, and dogs), self-assured (except about economics), and tremendously talented (but also notoriously arrogant). Apart from being a trained physicist, a self-taught statistician, and an important policy-maker, he was also an expert on Bengali poetry, particularly on the works of his mentor, Rabindranath Tagore.

*

In your book, you describe the Indian Planning Project as “an arranged marriage between Soviet-inspired economic planning and Western-style liberal democracy”.

I used this metaphor because during the time of the Cold War and superpower competition between the Soviet Union and the United States, planning and democracy were seen to be institutionally incompatible and ideologically contradictory. So India’s choice to put these two together was an experiment, a leap of faith by the Indian state.

* What was PC Mahalanobis’ equation with Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru?

As Nehru once put it, he preferred one technocrat to four bureaucrats. He was early to recognize that statistics would play an important role in economic development and planning. In the book, I describe a crucial meeting between Nehru and Mahalanobis in 1940 in Allahabad. They both stayed up past two in the morning discussing the role statistics could play in India’s economic development. It was a professional relationship that would blossom after Independence. Nehru privileged technocrats, and Mahalanobis wasn’t alone—Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai are other examples.

* Why does the Indian statistical system no longer command the respect it did?

It is because India is no longer seen as having a relatively independent, robust, and transparent statistical system. There has been an institutional decay due to insufficient funding, and more perniciously, on account of political interference. Earlier this year,

The Economist

carried a piece that described India’s statistical system as “crumbling”. It is because, as I say in my book, “good data isn’t always good politics”, and so we’ve seen National Sample Survey results suppressed, and other studies discontinued when it appears that they convey politically uncomfortable facts.