The China-brokered deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia, which was announced on March 10, to resume diplomatic ties and reopen embassies and missions within two months was unexpected. There was no prior buzz about it in Beijing; no news reports in foreign media predicted it; the Chinese party and official media such as People’s Daily and Xinhua, expectedly, reported it only after the information sluice gate was slid open.

The undisclosed negotiations took place for five days in Beijing between March 6 and March 10. Iraq and Oman hosted multiple rounds of dialogues between the two countries in 2021 and 2022, but there was no indication that a formal announcement will be made from Beijing.

There was no hint of a deal either when President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia in December to attend the first China-Arab states summit or when Iran’s leader visited Beijing last month.

The sequence of how the talks were engineered falls into place only in hindsight.

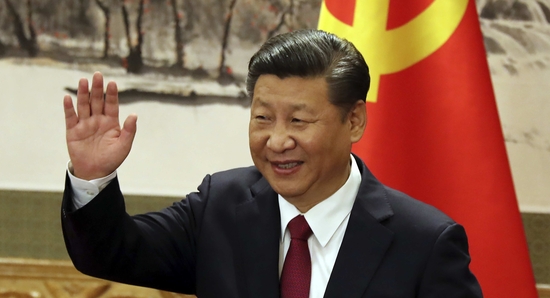

The timing of its announcement was finely calibrated: Right in the middle of the Two Sessions or the annually scripted meetings of the Communist Party of China (CPC) elites, who every year in March descend on Beijing dressed in black suits, starched military uniforms and mothballed ethnic finery to nod their allegiance to each decision taken by the leaders — now led by the very paramount Xi Jinping — inside the Great Hall of the People.

The symbolism of the talks was for all to see and interpret: The deal projected China as a global player under Xi as he secured — on the same very day – an unprecedented third term as China’s president, less than six months after he took over as CPC general secretary, also for a third term, at the 20th CPC congress in October.

The message for the captive domestic audience was that China’s “chairman” could now gather long-standing enemies at the same table to broker a peace deal of global significance. The attending CPC deputies and delegates went back to their provinces and counties across China at the end of the Two Sessions on March 13. They took with them the message of Xi’s rise in geopolitics, adding more layers to the cult of personality that’s been woven around him.

Remember also that Iran and Saudi Arabia are leaders — and bitter rivals — in the Islamic world, leaders of a world which instead of chastising China for its treatment of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, are now coming to Beijing to sort out unbridgeable differences between them.

The message to the world, especially to the Unoted States (US)-led West, was crystal clear too: The next five years will see Xi’s China increasingly taking on a role in global events. Wherever Washington is found wanting, Beijing will fill the vacuum or even take the lead.

The talks were led by China’s top diplomat Wang Yi and attended by Musaad bin Mohammed Al-Aiban, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of State, and Admiral Ali Shamkhani, Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council of Iran.

“Saudi Arabia and Iran have agreed to restore diplomatic relations and reopen their embassies and missions within a period not exceeding two months, and agreed to hold talks between foreign ministers to arrange for the exchange of ambassadors and explore ways to strengthen bilateral relations,” the three-country joint statement said on March 10.

Beijing is already a global power and geopolitical player, and it has been for years.

But brokering a deal between two rival Islamic countries, divided over many issues including the Shia and Sunni split, was quite the diplomatic accomplishment, which left Washington on the sidelines, looking in.

China’s influence — clout, maybe? — in West Asia is growing as the US’s ties with Saudi Arabia have considerably dampened in recent years. We already know about how openly hostile Washington and Tehran are against each other.

Beijing’s diplomacy goes hand-in-glove with trade.

Let’s take Riyadh first: China is Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade worth $87.3 billion in 2021.

“Saudi Arabia is China’s top oil supplier, making up 18% of China’s total crude oil purchases, with imports totalling 73.54 million tonnes (1.77 million barrels a day) in the first 10 months of 2022, worth $55.5 billion,” according to Chinese customs data, quoted by Reuters last December.

“Oil imports last year amounted to 87.56 million tonnes, worth $43.9 billion, making up 77% of China’s total merchandise imports from Saudi Arabia,” the report said.

China has also been Iran’s largest trading partner since 2010 with bilateral trade totalling $15.8 billion in 2022, up by 7% year on year, according to Chinese state media.

More importantly, Tehran and Beijing signed a 25-year cooperation accord in March, 2021 to “enhance comprehensive cooperation between the countries” to “tap the potentials in economic and cultural cooperation and make plans for long-term cooperation”.

Several reports have put the value of the deal upwards of $400 billion though the details of the agreement — surprise, surprise — remain undisclosed.

Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi was in China last month for a three-day visit, the first state visit by an Iranian president to the country in two decades.

Quite clearly Xi is trying to round up countries to form alliances against the West, which, at least, on the face of it tends to ask questions on uncomfortable topics like human rights. Beijing is not known to tie itself up in any such dilemma.

Make no mistake, the US’s influence is far from over in West Asia. Still, Beijing’s increasing presence in the region is a mark of its growing footprint: It’s an arena for Beijing and Washington to jostle.

“China’s brokering of the Iran-Saudi deal is emblematic of a regional realignment that no longer sees the United States as the only party in its calculations. It may be tough for the great power (the US) to accept and harder for it to readjust. But it may have no choice. The Middle East souk is now open for business in a way it’s never quite been before, and the United States isn’t the only customer,” Aaron David Miller, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former US State Department Middle East analyst, wrote for The Diplomat days after the deal was made public.

Here’s the thing: The outcome of the deal for Tehran and Riyadh will come later, if at all, but for Xi, it’s already a “win-win”.

Sutirtho Patranobis, HT’s experienced China hand, writes a weekly column from Beijing, exclusively for HT Premium readers. He was previously posted in Colombo, Sri Lanka, where he covered the final phase of the civil war and its aftermath, and was based in Delhi for several years before that

The views expressed are personal